Honest and Diverse Queer Character Writing

Note from Renee: This is a guest blog by my very good friend, social worker, and queer activist Nathaniel Gray. I invited him to write a post because it is important for Writing Diversely to be inclusive of all types of diversity, I am not LGBTQ+, and I believe giving fellow marginalized people voice. He was and still is my level headed, open-hearted, and empathetic teacher and advisor about LGBTQ+ matters. I hope you enjoy!

Honest and Diverse Queer Character Writing

I’m so excited to be writing a guest blog post for Writing Diversely. I strongly believe in the mission of this site and look forward to the effect it has on future work about minority characters. If you plan to write an LGBTQ+ character, make sure you know what LGBTQ+ means. It can be a lot to take in if you aren’t a part of the LGBTQ+ community. To get familiar with terms and definitions, head over to my site The Proud Path.

Disclaimer: As a gay man, I am going to write this post primarily about writing gay, lesbian or bisexual characters. Perhaps in future guest posts we can discuss characters’ gender identities as well.

So, how do we write complete LGBTQ+ characters? We need to recognize what an incomplete LGBTQ+ character is. While there are many tropes to choose from I want to address a huge on in particular: The Gay Best Friend (GBF). There are myriad examples of the handsome, funny, promiscuous, sassy, and typically white, gay best friend. There is even a movie called GBF with a character that fits nearly all of those descriptors. But why is this problematic?

1. Being gay doesn’t make you sassy and witty. This character type is often used as a comedic device (for example: Will and Grace, Modern Family) diminishing the other facets of their personhood. By making gay characters funny, we avoid their pain. If we write queer characters to be best friends and sidekicks, how do we tell their own story of anguish, discrimination, pain, rejection? These factors give queer characters honest inner turmoil and robust history that develop them into fully realized people.

2. The GBF is almost always white and young. Within the queer world are people from every country, skin color, religion, age group, etc. Yet, many narratives in popular culture would have us believe that all queer people are young white men in great shape. I would offer this challenge, what would your character’s experiences be like if they were LGBTQ+ and a refugee? Or a native speaker of Spanish? In a nursing home? Visibility of the full spectrum of queer people is lacking, and by introducing more queer characters outside of the majority into your story you provide space for queer youth who aren’t white men to see themselves reflected in literature.

3. Your LGBTQ+ character doesn’t always have to have the LGBTQ+ plot I’ve recently gotten onto the Shameless train (no spoilers!), and I’m a few seasons into the plot. I am so grateful that they tell difficult stories about coming out in communities that have inherent bias toward the queer community. However, it started dawning on me that Ian (the most prominent gay character) gets all of the show’s queer storylines. It would be refreshing if one of the straight male characters fell in love with a transgender person, or if someone else experienced oppression for their sexuality/gender identity. It is a type of tokenism, so I would offer that if you think up some really interesting idea about a queer plot, consider whether it must be used with your only queer character, or could happen to someone else.

Here are some examples of honest queer characters:

1. If you haven’t seen it yet, you should run to watch the movie Moonlight. The storytelling is captivating, and the central plot is one of sexuality confusion. But it allows for the lead character to be flawed, for us to see how the intersectionality of his identities as a black person, a possible queer person, and someone living in poverty all collide. The honesty and breadth of his whole person is what make the film truly robust and moving.

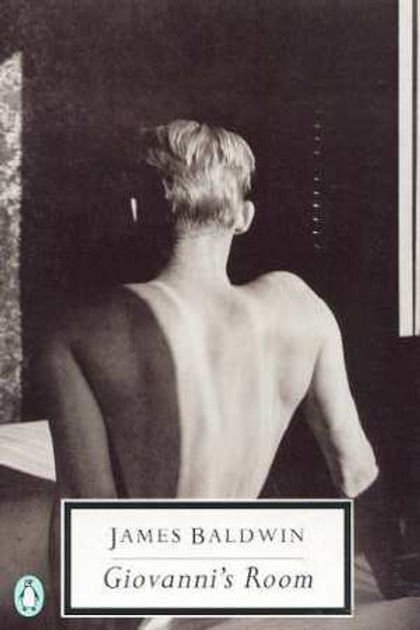

2. Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin and Call Me By Your Name by André Aciman are like time capsules for the queer experience in the mid/late-20th century. Many countries openly had laws against homosexuality, and even in America the act of two men having sex was technically against the law until 2007! Do your research on the laws and experiences of queer people in the time period your story is set. These stories are compelling, not just for the beauty of their story, but for the honesty and anguish in discovering that someone else feels like you, and finding a way to discuss it without ever saying it out loud.

My last piece of advice, include queer people in everything you write. I know that can seem a bit self-serving, but here’s why: in a recent study, nearly half of all teens surveyed this year said that they weren’t certain of their gender or sexuality. We’re starting to realize that there are a lot more of us out there than previously thought. That means that unless your central character goes out of their way to avoid LGBTQ+ people, they probably have a friend or two that identify as queer. Ultimately, as storytellers we have a duty to reflect the human experience with honesty, flaws and all.

Nathaniel Gray is the founder of The Proud Path, Fordham MSW ‘18, social worker and queer activist.